New insights on viewing dyslexia as an asset, phonological processing, and neural networks.

October is Dyslexia Awareness Month, and that means it's time to take a look at new research on how we can better support our students with dyslexia. We're highlighting three recent articles that expand our understanding of dyslexia and providing actionable best practices for you to implement with your students.

1. Dyslexia Without Deficits

In “2021 Dyslexia Research Updates,” we shared new research about students with dyslexia exhibiting high non-verbal creativity, and the practice of viewing dyslexia through an asset-based lens continues in 2022.

In research published in June, Helen Taylor and Martin David Vestergaard raise the possibility that people with dyslexia are especially gifted in explorative search, an open-ended, experimental practice where the searcher finds things they weren’t instructed to look for and didn’t know they would find. The researchers suggest that rather than having a neurocognitive disorder, people with dyslexia play an essential role in human adaptation, given their abilities to uniquely observe patterns and define and solve problems that neurotypical people may not see.

Explorative search may appear unwieldy or unfocused, but there is little doubt that it leads to deep and often collaborative learning. Moreover, observations may arise during explorative search that would likely not surface if the path to understanding was more straightforward. For example, during a basketball game, a player with dyslexia might notice that an opposing player always clears her throat before executing a specific move. Or, a mechanic with dyslexia might see that an engine part is not actually broken but affixed incorrectly because it is in an off-balanced position.

The authors of the article call to include more explorative learning in education and the workplace. They also suggest that institutions emphasize collaboration over competition.

In light of this new research, the more open-ended, exploratory, and collaborative projects you can give your students with dyslexia, the better! Try asking student groups to solve a real-world problem with many possible solutions. Examples include rising sea levels, educational inequality, food insecurity, automation-related job loss, or shrinking biodiversity.

Ask students to research and discuss the topic from many angles without any particular agenda or solution in mind. Once groups are relatively clear on the central issues and have learned about past attempts to mitigate or solve the problem, they can brainstorm creative, feasible solutions and present their best idea to the rest of the class.

Learning like this gives students with dyslexia the time and space to self-direct, explore, invent, and discover. It privileges process as much as outcome and celebrates students’ ability to creatively apply what they’ve learned to the world beyond school. And it draws on dyslexic students’ strengths, which is powerful given how often they’re made to feel less capable than their neurotypical classmates.

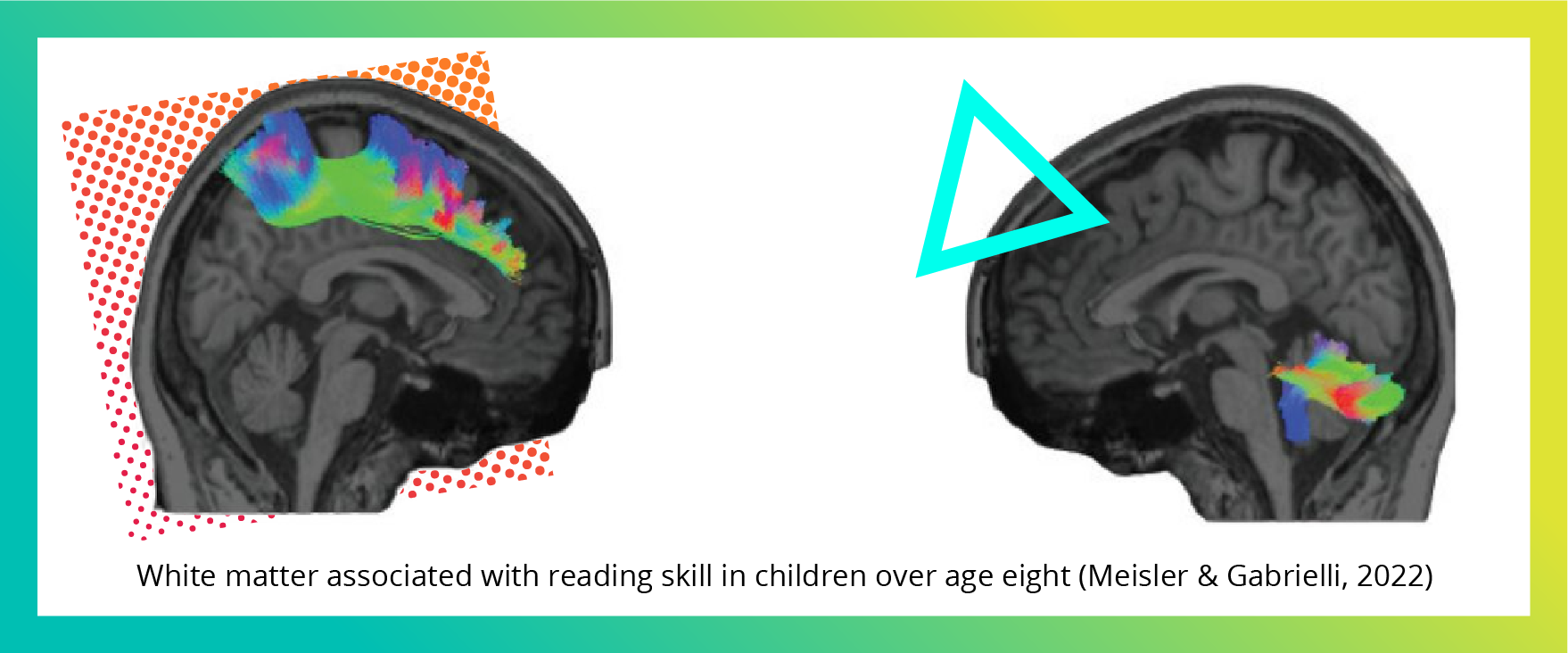

2. White Matter Might Matter

The links between white matter and dyslexia are something researchers have studied for a long time.

So what is white matter?

White matter can be thought of as the internet of the brain, says neuroscientist John Gabrieli of MIT. These bundles of nerve fibers connect different brain regions and allow them to communicate.

We know that the more white matter is used, the more it thickens, making communication speedier and more efficient. We also know that measuring white matter efficiency during reading lets neuroscientists determine which white matter tracts are often less developed in struggling readers.

In new research published in April 2022, Gabrieli and Steven Meisler compared the neural tracts of white matter thought to transfer information during reading in 686 children with various reading abilities. Researchers wanted to see if children with reading challenges, including dyslexia, generally had weaker white matter tracts than children who learned to read easily.

In children older than nine, stronger white matter connectivity was associated with an increased ability to sound out strings of vowels and consonants not recognized as real words but conforming to rules of language (nonword reading ability). Words such as “shemloo” and “nipaluna” can measure a student’s ability to segment words into specific speech sounds, attach sounds to letters, and blend those sounds into a word–the very skills many students with dyslexia struggle with.

The study indicated that, in older children (third grade and above), letter-sound correspondence skills are associated with greater white matter coherence in two important fiber tracts in the brain.

Teacher Takeaway

Teacher TakeawayThis research confirms what special education teachers and literacy specialists already know: letter-sound correspondence is crucial for reading achievement. It also suggests that subskills like phonological and phonemic awareness are likely just as important in building fluent readers.

Since slow, laborious decoding often taxes memory and attention, strengthening executive function skills is also crucial to teaching students with dyslexia to read. In fact, research suggests that students attain these skills optimally when they are taught in tandem. To strengthen both phonological awareness and underlying executive functions, teachers might consider implementing a supplemental reading program like Fast ForWord®.

3. Asymmetry Might Be a Brain’s Best Friend

No one has ever said that understanding dyslexia is easy.

And to muddy the waters more, research led by Mark Eckert from the Medical University of South Carolina and published in April 2022 engages the classic “nature vs. nurture” question as it pertains to reading ability and dyslexia. It suggests that both genetics and environment likely impact reading success.

Stronger readers are believed to have asymmetrical brains, where the left side is more developed than the right side. The question is whether these adept readers are born with more developed left brain hemispheres or if their brains become more asymmetrical as their reading skills advance.

Cerebral lateralization theory, a hypothesis that suggests that neural development is more closely tied to nurture than nature, states that while more asymmetric brains may facilitate better foundational reading skills, as these skills increase, brains become even more asymmetrical. This theory posits that a reader’s environment can and does actively change the wiring of their brain.

In contrast, canalization theory, which links neural development to biology, suggests that structural asymmetries are present at birth and directly relate to phonological processing, indicating a strong genetic basis for dyslexia.

dyslexia.

By analyzing more than 700 MRI scans, researchers confirmed that left brain asymmetry connected to non-word reading can increase over time, suggesting that reading ability is as least somewhat tied to experience and environment. However, asymmetry in some regions, including those specific to motor skills and performance monitoring, was largely unchanging, suggesting that the capacity to read well is partially biologically determined.

What do we do in the classroom when the “nature vs. nurture” question becomes more complicated with every new study published on dyslexia?

The main takeaway for teachers is that early interventions for students with unclear speech or difficulty with sound-letter correspondence should focus on strengthening phonological capacities. Research indicates that left hemisphere specialization increases as students learn to map sounds to letters. This correspondence is something all students can work to enhance, regardless of structural differences students with dyslexia may have in the regions of the brain that govern speech and self-monitoring.

Students With Dyslexia Make Gains with Fast ForWord

As we take a moment to acknowledge Dyslexia Awareness Month 2022, we want to celebrate the compassionate and innovative work you do with your students daily.

Still need a little inspiration?

Read about the success that students with dyslexia had in Barnegat Township School District in New Jersey with the supplemental language and reading program Fast ForWord. This innovative intervention developed by neuroscientists helped elementary schools make a 119% increase in advanced readers in just one year of use! We're excited to help your district be the next success story.

Dr. Martha Burns is an Adjunct Associate Professor at Northwestern University and has authored four books and over 100 journal articles on the neuroscience of language and communication. Dr. Burns’ expertise is in all areas related to the neuroscience of learning, such as language and reading in the brain, the bilingual brain, the language to literacy continuum, and the adolescent brain. Dr. Martha Burns is a Fellow of the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association and the Director of Neuroscience Education for Carnegie Learning.

Explore more related to this author

Before joining Carnegie Learning’s marketing team in 2021, Emily Anderson spent 16 years teaching middle school, high school, and college English in classrooms throughout Virginia, Pennsylvania, California, and Minnesota. During these years, Emily developed a passion for designing exciting, relatable curricula and developing transformative teaching strategies. She holds master's degrees in English and Women’s Studies and a doctorate in American literature and lives for those classroom moments when students learn something that will forever change them. She loves helping amazing teachers achieve more of these moments in their classrooms.

Explore more related to this author